May 11, 1931

Birthplace: Levice, Czechoslovakia

Holocaust experience: Levice ghetto; Auschwitz and Mauthausen concentration camps; death march

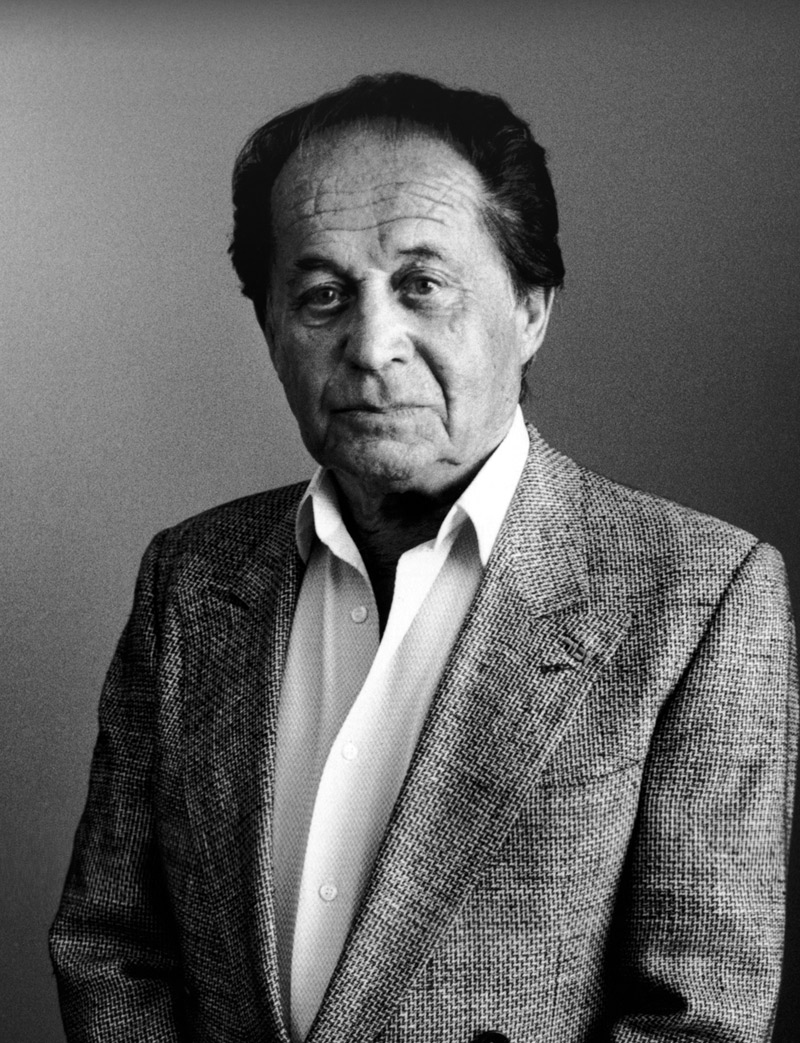

Michael “Miki” Popik Z"L

“I kept my family alive in my memory – I wanted to show them that I’m doing okay.”

Mike Popik was born Mikulas Popik on May 11, 1931 in Levice, Czechoslovakia, which had a general population of 22,000 and a Jewish population of 2,000. His father, William, was a sergeant in the Czechoslovakian army and co- owned a small trucking company, while his mother, Frida, was a homemaker. Mike had two brothers, Andrew and Gabi. Mike was seven years old when his life drastically changed on the night of Kristallnacht, “Night of Broken Glass,” November 9-10, 1938. His family heard of the antisemitic acts of violence taking place in Germany, and as the threat of war grew, the Czechoslovakian army began to mobilize. By the summer of 1939, Hitler was given the Sudetenland by Chamberlain, and the Hungarians had occupied Czechoslovakia.

In 1944, Mike’s family received orders to pack their belongings and move into the Levice Ghetto. In the ghetto, the Jews suffered under miserable conditions, with up to six families sharing a single room. After two weeks, the Hungarian army herded the Jews, including Mike and his family, from the Levice Ghetto to a railroad station in order to be relocated to labor camps in Hungary. The Jews were forced into cattle cars, 55 people to a car, with only one bucket per car to be used as a toilet. When the train finally reached its destination at three or four in the afternoon, Mike was able to look out the windows and see the Polish name Oswiecim. They had arrived at Auschwitz Concentration Camp, about 100 miles from the Czech border.

Read More

Upon arrival, the Jews were forced into three lines. Mike, his father, and older brother Andrew unknowingly said their last good-byes to his mother and younger brother Gabi, as they were sent to the gas chambers. A month later, Mike’s father and Andrew came to say good-bye, for they were being sent to Dachau Concentration Camp in Germany. Mike’s father made him promise that he would survive Auschwitz, and that he should volunteer for every work detail offered. That promise would eventually save Mike’s life. Mike never saw his father or brother again.

In July 1944, the Germans asked if any of the prisoners had mechanical experience, and in order to fulfill his promise to his father, Mike volunteered for the work detail. Mike later found out that those who had not volunteered were sent directly to the gas chambers. Mike was then sent to work in a huge cannon factory with 1,300 other Jews in Sasnovic, Poland. The living conditions in the labor camp were better than at Auschwitz, but by January 1945, Soviet shells were landing on the factory, and the Germans received orders to evacuate. Mike, along with the other prisoners, was forced to walk 12 miles through heavy snow to yet another railroad station to be evacuated to Mauthausen Concentration Camp in Austria. Life in Mauthausen was unbearable; Mike only received a small amount of food once a day and was constantly beaten. During one beating, a German SS officer kicked Mike in his back and sent him flying across the room. Years later, while in the Israeli Army, Mike would find out that the kick had ruptured and destroyed one of his kidneys. On May 5, 1945, a German announced over the loudspeaker, “the watch tower soldiers should leave,” and with that, the prisoners abandoned by the Germans and officially liberated by the 71st Infantry Regiment of the United States Army the next day.

After the war, Mike went to Palestine (pre-1948 Israel) and fought for two years during Israel’s War of Independence. In 1952, Mike met his wife, Esther, and during a visit to Mexico to visit his mother-in-law, they decided to apply for immigration to the United States. In 1958, Mike and his family were sent by Israel to go to France and to work in the oil fields. In 1963, the family came to the U.S. and then moved to California. In 1969, Mike purchased a car wash, became successful, and over the years owned many other car washes, mostly in Los Angeles, until his retirement in 2009. Mike and Esther are blessed with three daughters, Frida, Anita and Vivian, and six grandchildren, Evan, Josh, Alexa, Dayne, Samantha and Carly. As the only surviving member of his family, with the exception of an elderly aunt, Mike now speaks at the Museum of Tolerance “so I can show people that even with all of the hell I’ve been through, I can speak about it and tell future generations to never forget.”

Z”L stands for the Hebrew words meaning “may his/her memory be a blessing.”