April 13, 1927

Birthplace: Lodz, Poland

Holocaust Experience: Lodz ghetto, Trzebinia, Auschwitz-Birkenau

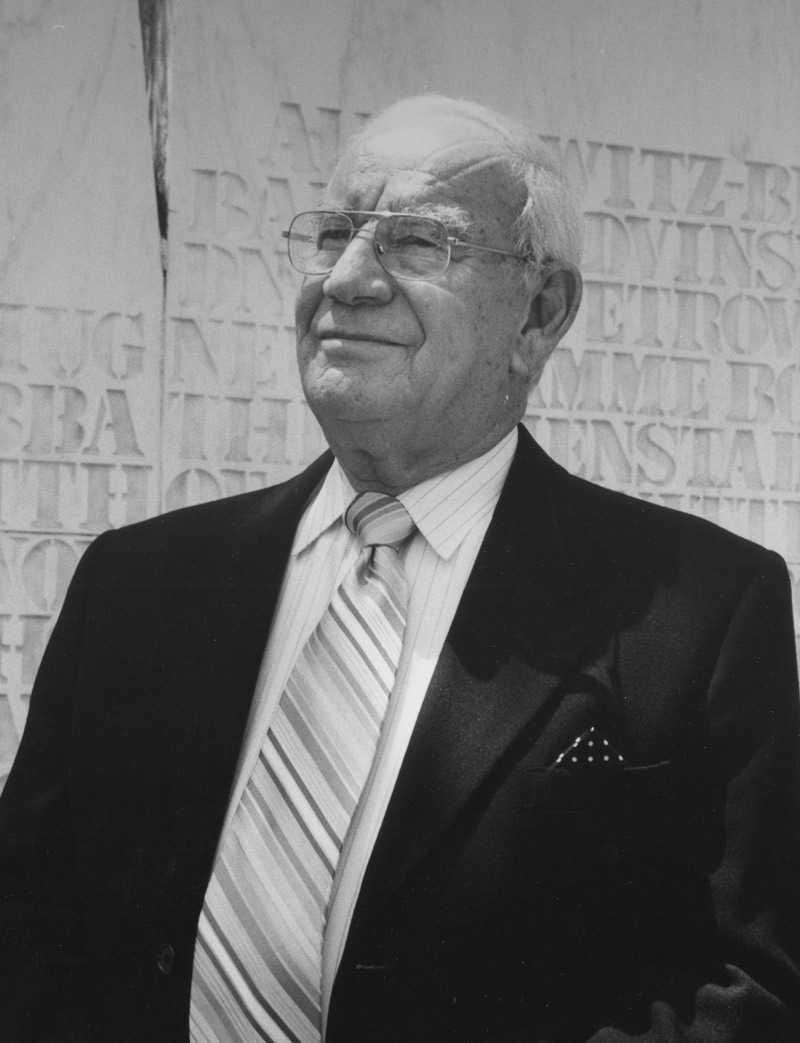

Jack Lewin Z"L

“The young people who come to our museum daily encourage me to tell my story of survival.”

Jack Lewin was born Jakób Lewin in Lodz, Poland on April 13, 1927. He was an only child. His father, Hersz Lipman Lewin, was a house painter and his mother, Dyna, was a seamstress. In 1939, when Jack was only 12-years-old, the Second World War broke out. Jack remembers seeing the headline on the Yiddish newspaper, which read “Hitler invaded Poland.”

In 1940, Nazi soldiers ordered the Lewin family to leave their home. They loaded all of their possessions onto a horse-drawn cart and walked to the Lodz Ghetto to live with Jack’s maternal grandparents. In the ghetto, everyone was forced to work for the German war effort, and Jack’s mother worked as a seamstress in a uniform factory. However, his father did not find work immediately, and as a result, they did not have enough money for food. In desperation, his father, who was 41-years-old, volunteered to work at a labor camp 100 kilometers outside of Lodz in May 1941. That was the last time that Jack saw his father. For Jack, living in the ghetto was “the hell that lasted the longest,” since conditions in the ghettos were sometimes worse than in the camps. The hunger he experienced while in the ghetto was devastating, and people died daily of starvation and disease.

Read More

In July 1944, the Germans began to liquidate the Lodz Ghetto. Jack and his mother were put on cattle cars and taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau Death Camp. He was separated from his mother immediately as Dr. Mengele, known as the “Angel of Death,” stood in front of the line and pointed his mother in the direction of the gas chambers. She was only 44-years-old but looked much older because she was so swollen from hunger. Jack was sent to Birkenau, the slave labor camp adjacent to Auschwitz. His head was shaved, and he was given a prisoner’s uniform. He was assigned to the area known as the gypsy camp, which had been liquidated of gypsies some time earlier. In this camp there were 1,100-1,200 other young adults. They slept like sardines with blankets on concrete floors. Every morning at 2:00 a.m., they were woken up and kicked out of the barracks for roll call. After two weeks in Birkenau, Jack was sent to the showers, given a new uniform, and tattooed with the number #B-10237.

Soon after, Jack was sent to a sub-camp of Auschwitz located in Trzebinia, Poland. It was the prisoners’ job to rebuild the bombed out oil refinery. The work was intense and backbreaking, and Jack often had to carry bricks or push wheelbarrows of cement.

In January 1945, the Germans liquidated Trzebinia, and Jack was forced on a Death March back to Auschwitz-Birkenau, arriving in mid-January. The Soviet Army liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau only ten days later on January 27, 1945. When Jack asked a Soviet soldier what he should do, the soldier replied, “What do I care? Go where you like.” After five years behind electrified wire, Jack decided to stay in the camp where he was given food and a bed.

He remained in Auschwitz for about a month and then decided to return to his hometown of Lodz in March. Tragically, Jack discovered that no one in his family had survived the Holocaust. He found work and was hired as a runner for a newspaper, taking articles from the editors to the printers. He then worked in a restaurant, before eventually working in the kitchen for the American Air Force. In 1947, Jack married Regina (née Szwarcfeld), who also was a Holocaust Survivor from Czechoslovakia. In 1950, upon receiving papers to travel to either the United States or Australia, Jack and Regina decided to immigrate to Australia. They resided in Melbourne for fifteen years and then moved to Los Angeles in 1965. Jack was a shipping clerk and then began his own business selling ladies sportswear. They are blessed with two daughters, Dinah and Sylvia, a granddaughter named Perla, and a great-grandson named Avi.

Jack speaks at the Museum of Tolerance to discourage prejudice and to make his story accessible to people of all ages.

Z”L stands for the Hebrew words meaning “may his/her memory be a blessing.”